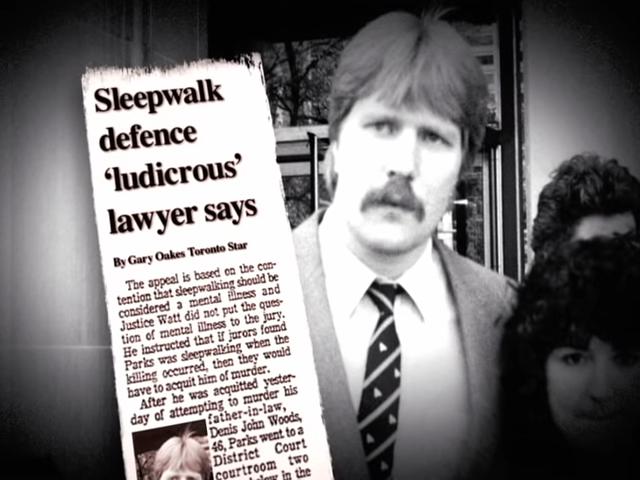

In one of the most baffling and controversial murder cases in modern history, a Canadian man named Kenneth Parks walked free after claiming he killed his mother-in-law — while sleepwalking.

On May 24, 1987, the 23-year-old father of one drove 14 miles in his sleep, arrived at his in-laws’ home in Scarborough, Ontario, and brutally attacked them with his bare hands. His mother-in-law, Barbara Woods, died instantly. Yet moments later, a dazed and blood-soaked Parks staggered into a nearby police station and confessed, saying the chilling words: “I think I’ve killed someone… my hands.”

The case quickly made headlines across the globe. Prosecutors argued that Parks’ actions were deliberate — that no one could commit such a precise, violent act while unconscious. But defense lawyers unveiled a groundbreaking argument: Parks was sleepwalking.

Medical experts diagnosed him with non-REM sleep arousal disorder, a rare condition that causes individuals to perform complex — and sometimes dangerous — actions while still asleep. EEG tests confirmed that Parks had suffered from chronic sleep disturbances for years, including night terrors and extreme stress, triggered by job loss and gambling debts.

After weeks of expert testimony, the jury delivered a stunning verdict: Not Guilty. They believed Parks was unaware of his actions — legally absolving him of responsibility. The courtroom gasped. The public erupted. And the case became a legal landmark, redefining the boundaries between crime, consciousness, and culpability.

Even decades later, the “Sleepwalking Murderer” case continues to haunt psychologists and legal scholars alike. Could the human mind truly commit murder while asleep? Or did Kenneth Parks escape justice through a loophole science could not fully explain?

Since his acquittal, Parks has lived a quiet life — never again showing signs of violence or sleepwalking. But the echoes of that night in 1987 still raise a chilling question: what happens when your body acts without your mind?